Confronting the National Opioid Crisis

A Multipart Series

- Introduction

- A Call to Action

- Strategies for Smarter Service

- Expanding Naloxone Awareness and Use

- Doubling Down on Drug Disposal

- Delivering Straight Talk on Opioids

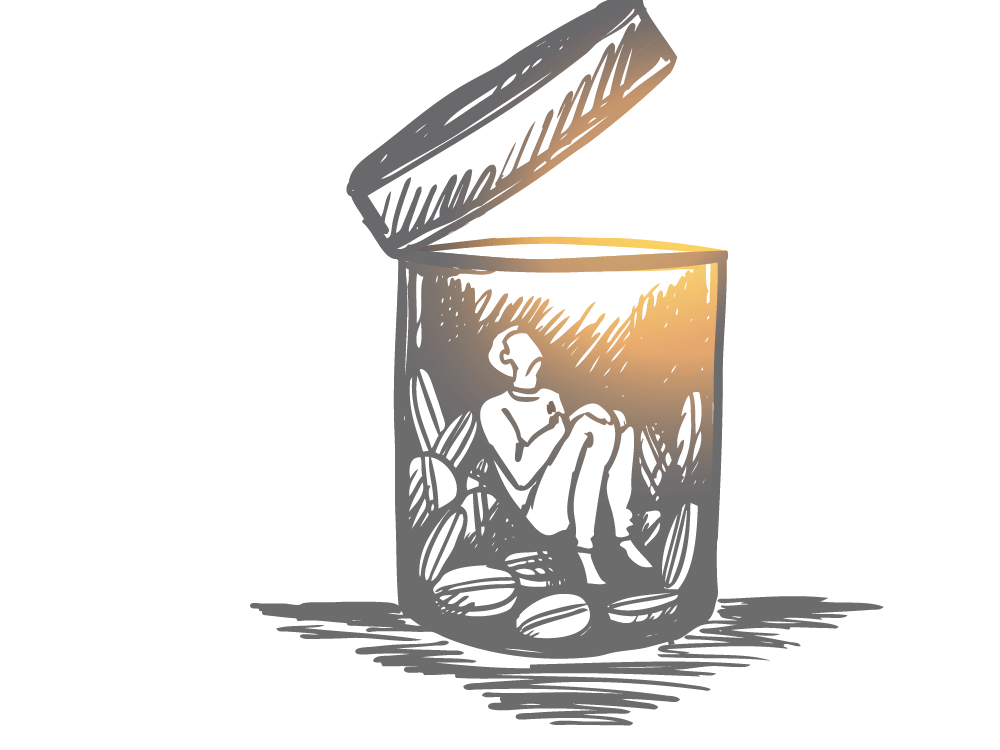

Doubling Down on Drug Disposal

Students are helping curb diversions and create new habits via safe medication disposal.

By Athena Ponushis

One of the greatest roles pharmacists play in the opioid crisis may be changing the public mindset about saving medications. Schools of pharmacy are reducing the accumulation of prescription medications in medicine cabinets, minimizing the risk that those drugs might be stolen and abused, by having student pharmacists connect with the public at drug take-back events to convince people that it is unsafe to keep prescriptions that are no longer needed. “The biggest motivator for safe medication disposal is really understanding where the problem of our opioid epidemic and controlled substance diversion comes from: legitimate prescriptions that have gotten into the wrong hands,” said Dr. Krystal Riccio, associate professor of pharmacy practice at Roseman University of Health Sciences College of Pharmacy.

Patients are motivated to give back their unused medications after seeing the connection between addiction and diversion of prescriptions, and student pharmacists are motivated to continue the cause, knowing that they are making an enormous impact. Students at the St. Louis College of Pharmacy (STLCOP) having been doing door-to-door drug take-backs since 2011, collecting more than 2,200 pounds of medications. The school was also a founding member of the Missouri Prescription Pill and Drug Disposal (MO P2D2), which has positioned more than 25 medication disposal boxes across the region. Between these efforts and the national take-back days organized by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), 124 tons of medication have been collected in the St. Louis metro area since 2011.