Pharmacy school curricula are prioritizing patient safety to prepare future pharmacists for their vital role in keeping patients safe.

By Jane E. Rooney

It’s something we often take for granted, because we assume health professionals are being vigilant and have been trained to consider crucial questions such as: Has the patient received the correct medication? Is the proper dose indicated on the prescription label? Will the medication have any harmful interactions with other prescriptions being taken? Patient safety is paramount, but most people probably don’t give it much consideration when the healthcare system is operating as it should.

The reality, however, according to World Health Organization (WHO) statistics, is that four out of every 10 patients are harmed in primary and ambulatory care settings. The most detrimental errors are related to diagnosis, prescription and the use of medicines.

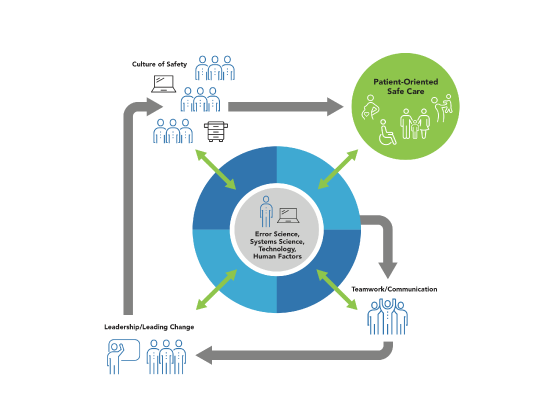

WHO defines patient safety as the absence of preventable harm to a patient during the process of healthcare and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with healthcare to an acceptable minimum. Guidance from the organization indicates that “clear policies, organizational leadership capacity, data to drive safety improvements, skilled healthcare professionals and effective involvement of patients in their care, are all needed to ensure sustainable and significant improvements in the safety of healthcare.”

Pharmacists clearly play a crucial role in keeping patients safe. The Alliance for Patient Medication Safety (APMS) is a federally listed Patient Safety Organization (PSO) that works with independent and regional chain pharmacists on patient safety initiatives. Its mission is to help community pharmacies implement and maintain continuous quality improvement programs to improve patient care. Their programs help pharmacies comply with health insurance and state and federal quality assurance requirements.

“We emphasize that every pharmacy put in place a learning environment instead of a punitive environment in order to build a safe, just culture,” explained Tara Modisett, executive director, Alliance for Patient Medication Safety. “When a strong safety culture exists where the staff feels empowered to say ‘hey, this is a workaround or a process that isn’t the safest practice,’ and their input is valued and respected, good conversations can result. Most community pharmacies already deliver the safest care they know how to but PSOs provide resources and help to take it to a higher level.”

Last year, the Patient Safety Movement Foundation developed a core curriculum—available for free to all professional healthcare schools—to teach patient safety from the first professional year through residency. Chapman University School of Pharmacy (CUSP) has committed to this curriculum, which will begin during the first year of school with the goal of creating entry-level practitioners with a broad knowledge base and skills that can be used to improve patient safety. “We know Adverse Drug Effects are the fourth leading cause of death in America. We also know pharmacists are in communities within five miles of every citizen,” said Dean Ronald P. Jordan. “CUSP faculty are fully committed to ensuring our students become expert sources of safety information. By adopting Leadership in Patient Safety Education as a pillar of our school’s strategic plan, we seek to lead pharmacy schools to teach students and other health professionals to think safety first.”

Both the CAPE Outcomes and the 2016 Accreditation Standards outline the topics student pharmacists must learn to optimize the safety and efficacy of medication use systems. “All pharmacy schools emphasize patient safety and talk about it in a broad sense,” said Dr. Mary Douglass Smith, Presbyterian College School of Pharmacy’s interim executive director of experiential education. “I think being able to share errors and dig into more specifics will help students be more prepared for what the profession will be like. There will be errors but this is how we mitigate them and solve them. These are practical ways to put safety at the forefront of practice.”

Steps Toward Better Communication

Dr. Catherine Hatfield, director of interprofessional education and clinical associate professor, University of Houston College of Pharmacy, said the main thing pharmacists can do to ensure patient safety is learn to speak up. “When you see something that doesn’t sit right with you, you have to be able to speak up and be a team member if the dose isn’t right or the drug isn’t right,” she noted. “If you are too afraid to speak up about an error, you are a part of the problem.” Hatfield attained the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Patient Safety Certification several years ago and decided the information she learned was important enough to pass along to student pharmacists. What began as an elective became a required course in Houston’s curriculum in 2019.

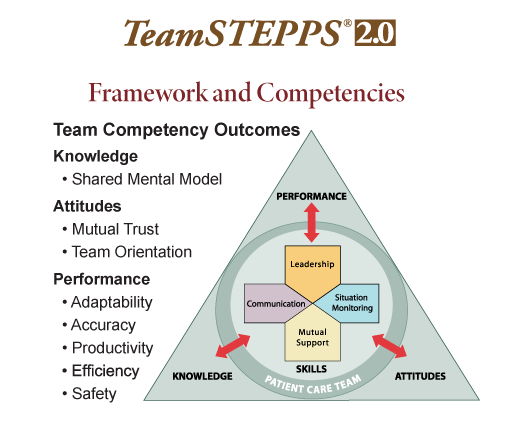

Another key part of the curriculum is TeamSTEPPS, a standardized framework of communication to improve patient safety that originated with the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It is an evidence-based set of teamwork tools, aimed at optimizing patient outcomes by improving communication and teamwork skills among healthcare professionals. “I’ve been teaching it in our curriculum since 2014. It is something that should be taught to all health professions,” she said. “It’s about learning how to communicate and speak up to reduce communication errors, which is one of the biggest fixable patient safety issues in healthcare today.” She believes we need to get away from training healthcare professionals in silos and that there should be a movement to get TeamSTEPPS into every pharmacy school, which will ultimately lead to improved patient safety.

“There are tools within TeamSTEPPS that train everyone how to communicate,” she continued. “One is called the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) model. If a pharmacist can learn to speak that way to a doctor or nurse and that other health professional has been trained in SBAR, they can communicate effectively. CUS (concerned, uncomfortable, safety issue) is another one. If you get frustrated or upset, you need to figure out a way to communicate with that individual and enter into a dialogue so you can come to an agreement to figure out what is best for the patient. You need to advocate for the patient. When you’re upset and feeling like you’re not being heard, this allows you to express why you’re concerned. The safety issue should stop everything and everyone should come to an agreement and decide if things are proceeding the way they should be.”

Another main focus in the curriculum is learning to recognize errors. “A lot of what patient safety involves is how do we fix system errors so they don’t happen again,” Hatfield said. “We’ve got electronic records so you don’t have transcription errors, but what can you do to prevent the onset of errors? A lot of that is communication. The IHI modules and the patient safety IPE force students to practice speaking up and learn the roles within medicine, nursing and pharmacy and how they work together to improve things for patients.”