He thought about the role of pharmacy, the need for medications and the impact on patients and their families. “A lot happens when a person leaves the pharmacy and takes that bottle of pills with them,” he said. “There is stress inside the household about that medication and whether it is taken properly. A lot of social pharmacy is brought to the table.”

Kevin Kling, the play’s author and a Minnesotan playwright who has contributed to NPR’s All Things Considered, said, “We all think we are logically driven. It’s the reverse: we are emotionally driven people.” That emotion, mixed with the clinical force, uncertainty and hope are what he wanted to convey. A preliminary version of the play was performed this past February by students in a class taught by Kuftinec and Luverne Seifert, head of BA theatre performance in the Department of Theatre Arts & Dance and the play’s co-director. Eight performances of “Rare: Stories of Dis-ease,” are slated to run in cities across Minnesota, Wisconsin and North Dakota from Oct. 8 through 23.

Raising Awareness

A rare disorder is a disease or condition that affects only a small number of people; “orphan” drugs target those diseases. More than 7,000 diseases in this country are considered rare, affecting one in 10 Americans and their families—or 30 million people. Too often, diagnosis is delayed and there are relatively few available effective treatments, which UMN researchers and others are trying to change. While there are drugs for some diseases, many patients still face obstacles receiving treatment. Despite the number of people with rare diseases, many conflicts and contradictions exist. Many rare diseases are life-threatening, and the delay in diagnosis results in delays in treatment.

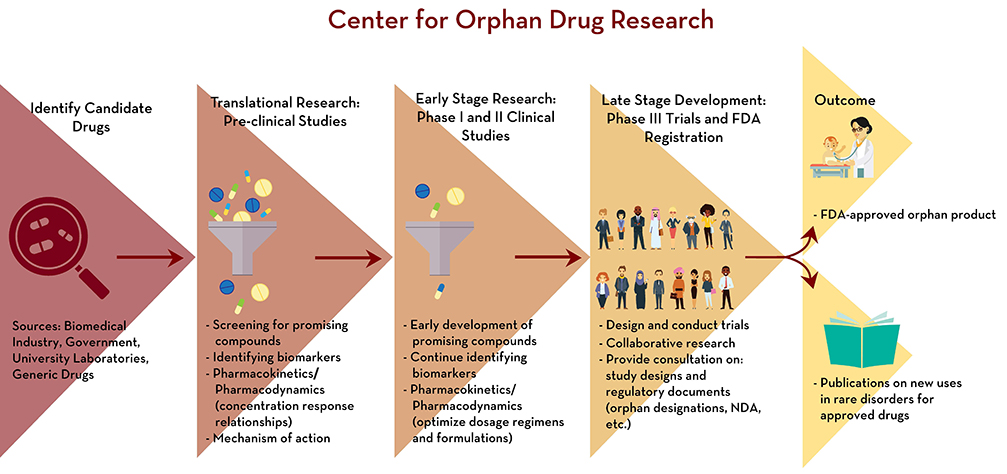

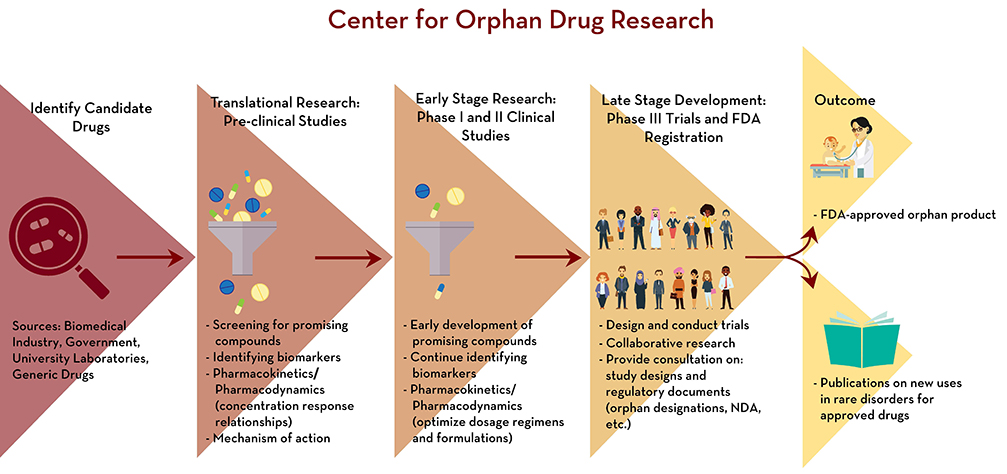

Historically drug companies did not pursue development of orphan drugs due to poor economic returns, but thanks to the 1983 Orphan Drug Act and other factors, that appears to be changing. In addition to the pharmaceutical industry, many academic institutions are making substantial investments in research infrastructure, establishing new programs for drug discovery and development, including orphan drugs.

“Academic pharmacy can make significant contributions to orphan drug development given our expertise in drug design, delivery systems and clinical pharmacology,” said Dr. James Cloyd, III, director of the Center for Orphan Drug Research and a professor in the Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. He has been working on rare diseases at the university since the 1970s, initially focusing on epilepsy, a passion of his.

With Cloyd and colleagues, the UMN College of Pharmacy has developed into one of the leaders studying and researching orphan drugs with a focus on rare neurological disorders in children. Over the past several years, the Center has experienced substantial growth, expanding its research to include seizure disorders, spasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Cloyd also noted that pharmacy schools have the opportunity to bridge gaps in their instruction about orphan drugs and rare diseases.

“Sometimes our faculty will talk about a condition, such as sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis, and not think of them as rare, but they are,” he observed. “It is increasingly apparent to me that we need to do more to raise awareness among our pharmacy graduates about rare diseases. The likelihood that a pharmacist will provide pharmaceutical care for rare diseases is increasing, whether you are at Walgreens or a major medical center.”

“The topic of orphan drugs includes some categories that are not covered in much detail in pharmacy schools,” he continued. “We need to prepare our students for the practice of pharmacy in the future. They need to understand what the patient and family are going through not only in terms of the medical aspect, but also the psychological, social and economic impact. We want to make sure our graduates are ready and prepared.”

Learning opportunities for students at CODR range from research studies to seminars to advocacy programs, Cloyd said. “The center offers directed studies, summer research assistantships and an elective APPE research rotation.” The Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology (ECP) graduate program includes a course on Regulatory Issues on Drug Research that presents an introduction to the Orphan Drug Act. This fall, he added, ECP will provide a module on orphan drug development in a course on Principles of Clinical Pharmacology, which is available to graduate and Pharm.D. students.

Cloyd said that CODR’s research on orphan drugs and rare diseases is increasing, as is its coordination with drug companies in developing specialized medication. He pointed out that CODR’s mission is to “improve the care of people who have rare diseases through research on new drug therapies, education of health professionals and health profession students and contribute to the discussion and formulation of public policy relating to rare diseases and orphan drugs.”

That mission correlates with the play. As they put the final touches on the script, Kling and others said that the obstacles that patients face in receiving care will be addressed. An example is sickle cell disease, a group of inherited blood disorders, which impact minority groups, particularly the Black population. For people in pain with sickle cell disease, the ailment is not always obvious to an outsider. The result is that some patients have faced discrimination and have been accused of feigning pain.

With rare diseases, “patients become experts because they have to be, and there is importance in moving from isolation to a community. That is a kind of healing, a story we heard time and time again,” said Kuftinec. Access to education is not only important for patients and families but doctors as well, who too often may be putting on “blinders and not able to see rare diseases.”

Seifert said patients and families need to know that others are going through similar experiences. He mentioned the case of a young mother struggling with a mysterious illness. “The doctor said, ‘You know as much information as we know,’” Seifert related.

Cloyd noted that studying rare diseases means examining “precision medicine, picking the right drug and right dose and then maintaining that dose in the blood level over time.” Looking at the expansive accomplishments of the university, he said, “I think we have made some important contributions to the rare disease community.” He emphasized that advances in biomedical sciences have resulted in an acceleration of orphan drug development, “resulting in hope for the future. In fact, we have seen miracles taking place with respect to orphan drugs and gene therapies for rare diseases.”

In her classes, Dr. Reena Kartha, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy and an associate director of Translational Pharmacology at CODR, sees awakenings among students each day as she teaches her freshman course, “Rare Diseases: What It Takes to be a Medical Orphan.” Kartha said she has made it a point in her directed studies course and clerkship to have student pharmacists interact with rare disease patients. Inevitably, emotion becomes an important element in the educational scope of instruction. After learning about orphan drugs and rare diseases, one of her students observed, “I just realized all my complaints are so trivial, especially after understanding what others are going through.”

Joseph A. Cantlupe is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.